NASA’s

Cassini spacecraft has been voyaging through the solar system since October

1997. It went into orbit around Saturn in 2004 and has since taken thousands of

images of the planet, its rings, and its many diverse moons. But on 15

September, the craft will end its mission by crashing into Saturn.

As the

Cassini mission draws to an end, New Scientist looks back at some of the most

impressive images that the spacecraft has sent back to Earth.

Saturn

approaching its northern summer

Taken in

April 2016, this set of stitched-together images reveals the beginning of the

summer solstice in Saturn’s northern hemisphere. Increased sunlight causes

rising hazes that blur some of the planet’s swirling features and mute the

bluish hues more visible in the northern winter.

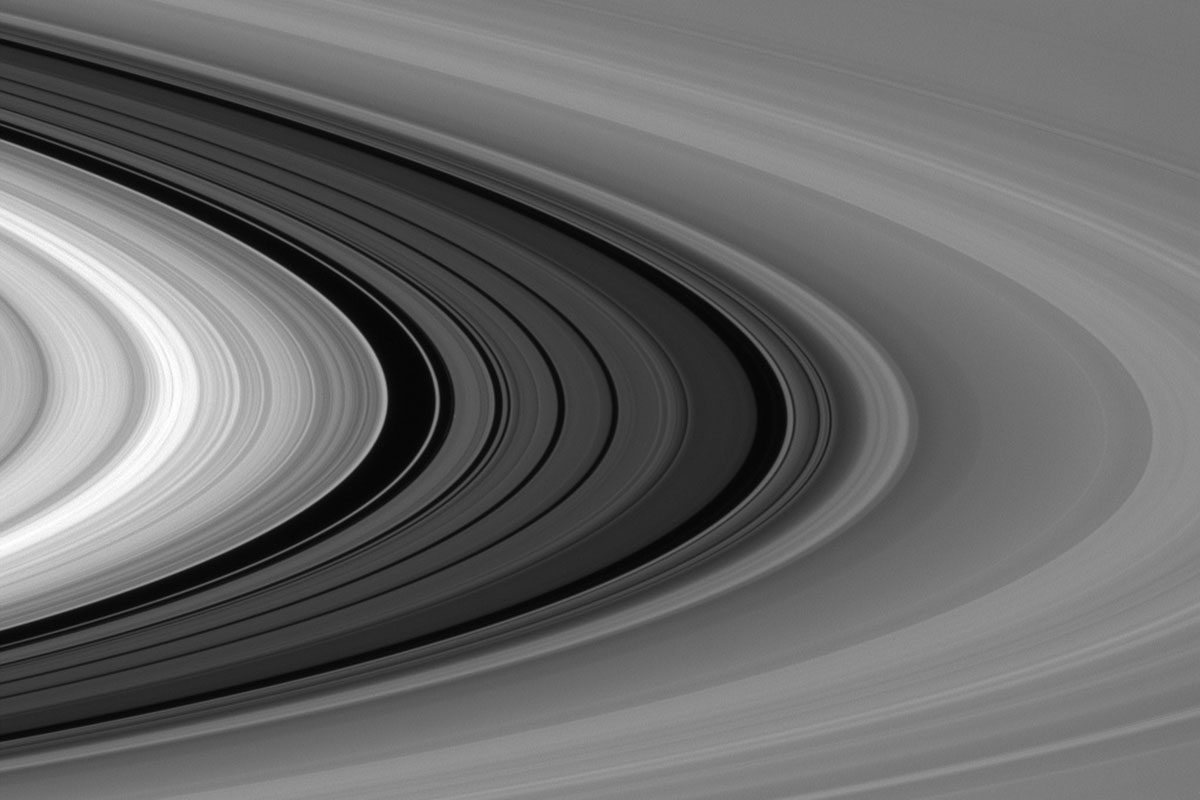

Saturn’s

rings

Cassini

marked scientists’ first opportunity to study the temperature and composition

of Saturn’s rings from an orbit around the planet. The rings are only about 10

metres thick and made mostly of ice chunks ranging in size from microns to

metres across. This image was taken from about 1.2 million kilometres beyond

Saturn’s surface.

Enceladus

and its geysers

Before we

sent Cassini on a path past Enceladus, scientists expected Saturn’s

sixth-largest moon to be frozen solid. But these geysers spewing from its south

pole indicate a buried sea that could span the whole moon. Later on, Cassini

sailed through the jets and found that they contain nearly all the required

ingredients for life, making Enceladus’s subsurface ocean a strong contender

for potential life in our solar system.

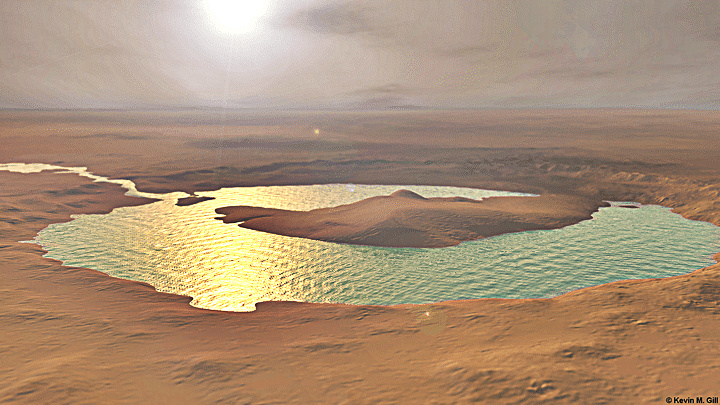

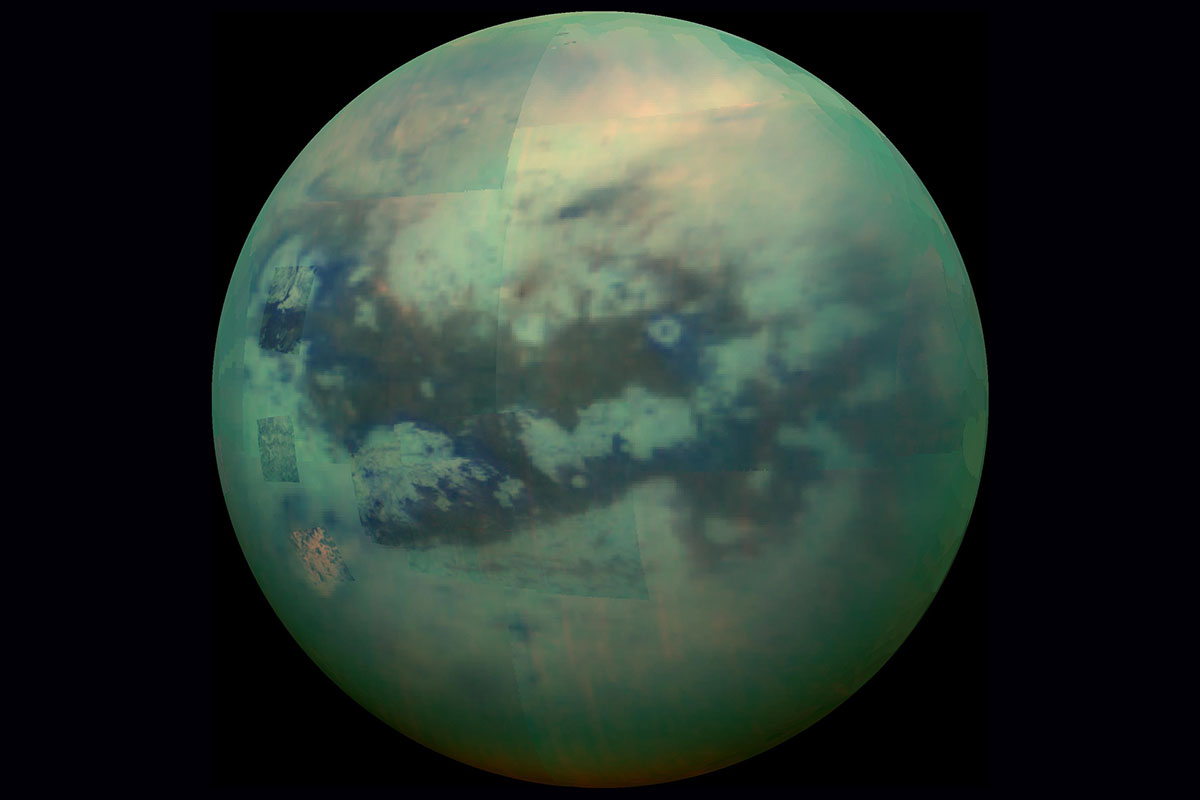

Titan

Saturn’s

largest moon, Titan, also has serious potential for hosting microscopic life.

Although visible light cannot peer through this moon’s thick, hazy atmosphere,

infrared observations like the one seen here reveal its liquid methane seas.

Titan is freezing cold and has no liquid water, but Cassini has seen some

promising signs for the possibility of life there.

Saturn’s

polar hexagon

Saturn’s

North Pole hosts an enormous spinning hexagon almost 25,000 kilometres wide.

Its constant churning is generated by a powerful wind current that makes the

hexagon rotate once every 10 and a half hours around the huge storm at its

centre.

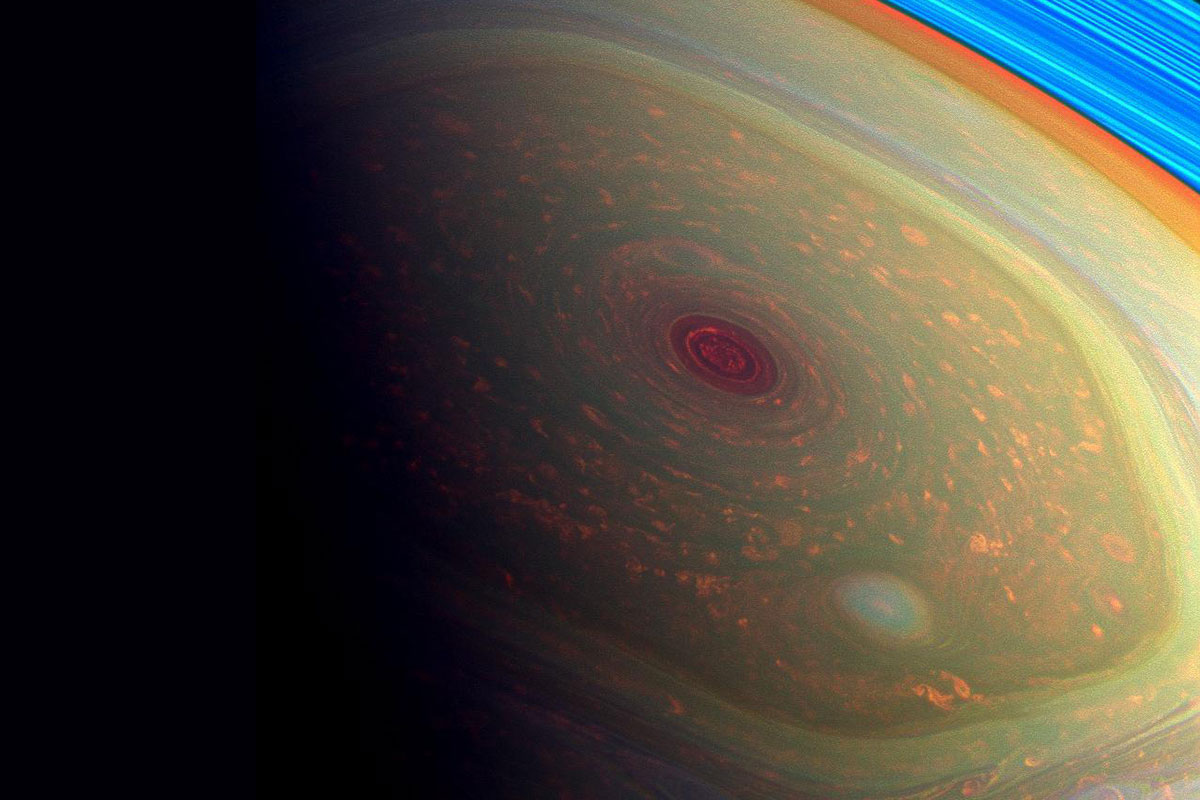

Saturn’s

Rose

In this

false-colour image of the eye of Saturn’s north polar vortex, red indicates low

clouds and green high ones. This colossal hurricane, about 4000 kilometres

across, whirls at Saturn’s north pole year-round, but nobody knows what keeps

it spinning.

Daphnis

makes waves

Saturn’s

moon Daphnis is only 8 kilometres across, but can still make waves. As Daphnis

orbits, its gravity causes ripples in the rings. Some particles from the rings

also stick to the miniature moon, building up a ridge around its equator – a

process that happens on several of the moons that surf the planet’s rings.

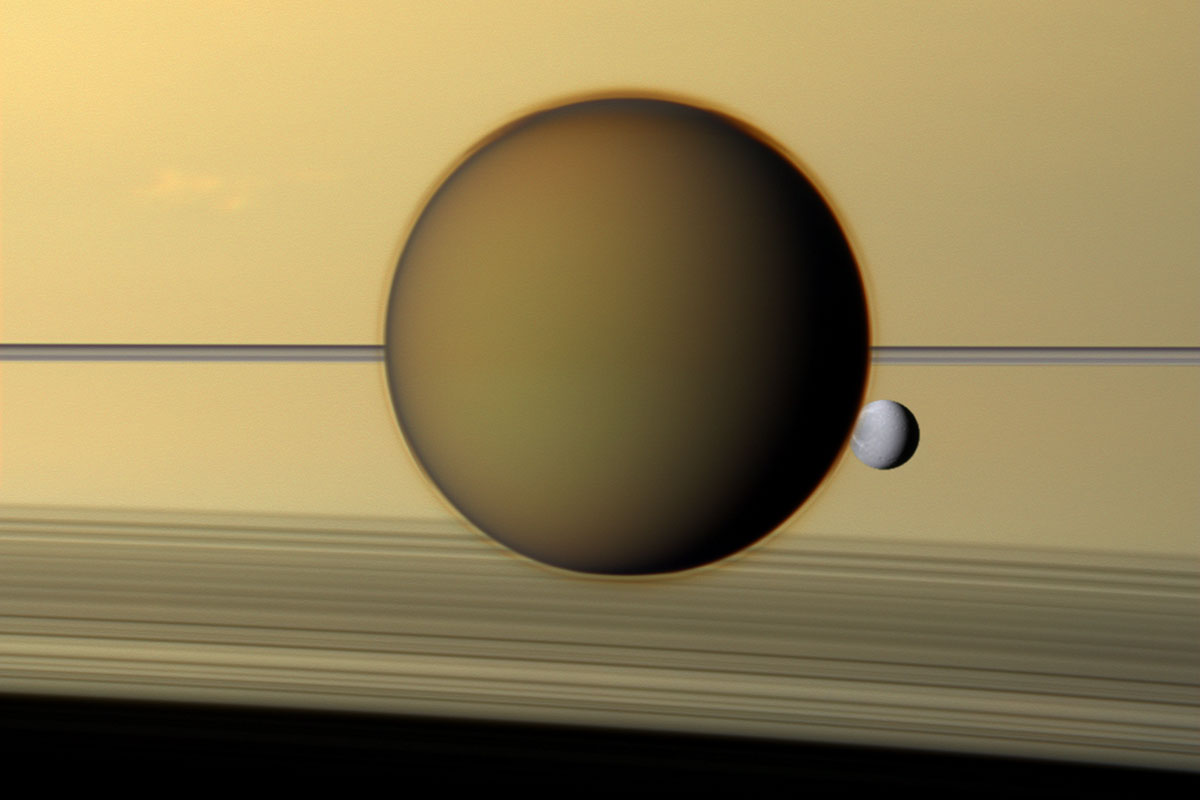

Titan,

Dione, and Saturn’s rings

Saturn has

62 confirmed moons. Two of them, Titan and Dione, pose here against a backdrop

of the planet’s rings. Titan’s thick orange smog makes it the only known moon

with a significant atmosphere. Most of Dione is water ice, but Cassini detected

hints that it may conceal a liquid water ocean.

Backlit

Saturn

In July

2013, Cassini flew into the shadow of Saturn, pointed its cameras back at the

planet, and took a series of images with the sun’s light filtering through the

gaps in the rings. This mosaic uses 141 of those pictures.

Earth from

Saturn

As Carl

Sagan wrote, “That’s here. That’s home. That’s us.” The pale blue dot floating

under Saturn’s rings is Earth from 1.44 billion kilometers away. With no more

spacecraft exploring the outer solar system, it’s not a view we’ll see again

soon.

Post A Comment:

0 comments: