Touching a

star isn't easy. The sun is an enormous, searing-hot orb of plasma that

generates a chaos of magnetic fields and can unleash deadly blasts of particles

at a moment's notice.

But that is

precisely what NASA plans to do – 24 times or more – with its car-size ParkerSolar Probe (PSP).

The goal of

the AU$2 billion (US$1.4 billion) mission is to edge within 4 million miles

(6.4 million kilometres) of the sun, which is close enough to study the star's

mysterious atmosphere, solar wind, and other properties.

Information

gathered by the probe may help space weather forecasters better predict violent

solar outbursts that can overwhelm electrical grids, harm satellites, disrupt

electronics, and possibly lead to trillions of dollars' worth of damage.

The

spacecraft is slated to launch from the Florida coast on Saturday at 3:33 am

EDT, should weather cooperate, though NASA has through August 23 to fire off

its probe. PSP will reach the sun a few months after launch.

Here are

some of the brutal conditions and tremendous challenges NASA's probe will have

to survive to pull off its unprecedented mission.

The tricky

process of touching a star

The first

hurdle PSP needs to clear is Earth itself.

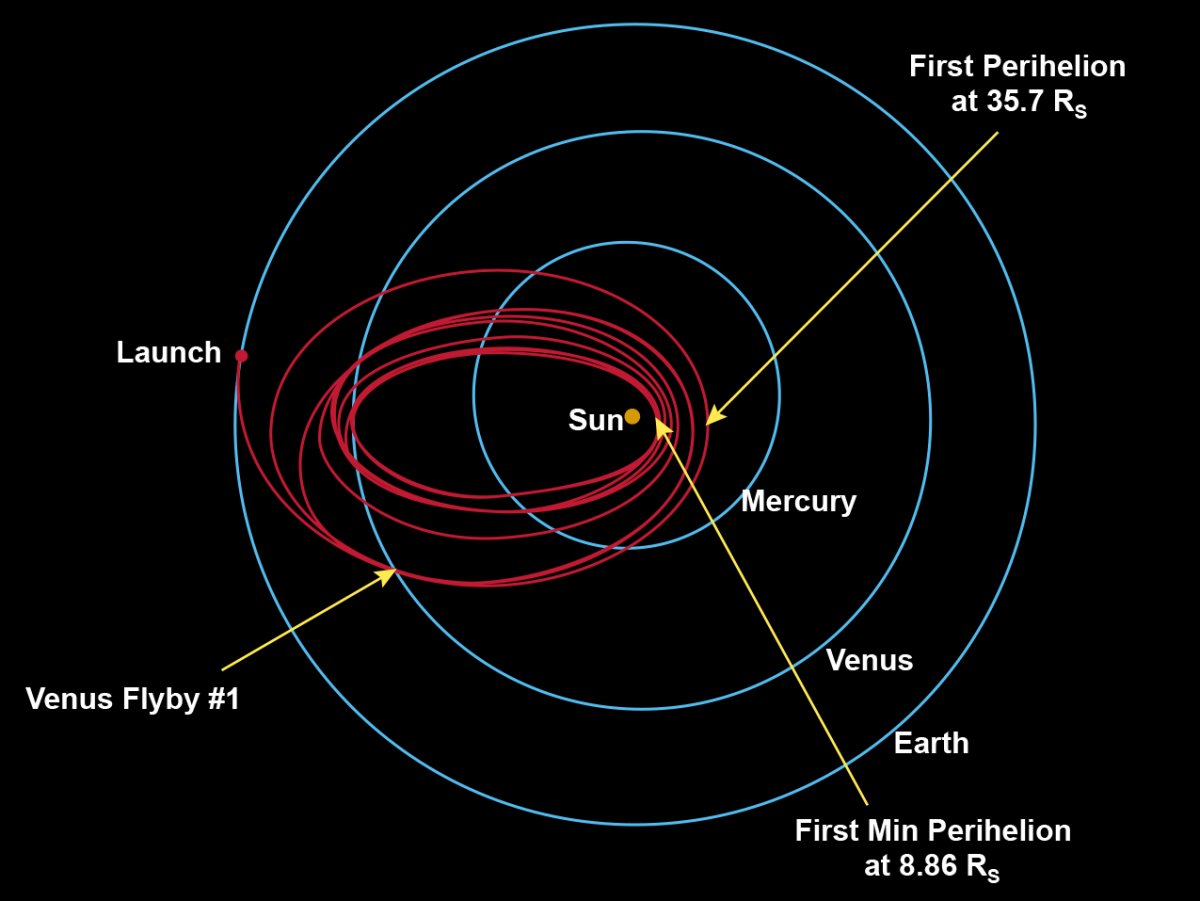

The orbital

path that NASA's Parker Solar Probe will have to fly (Johns Hopkins University

Applied Physics Laboratory)

The orbital

path that NASA's Parker Solar Probe will have to fly (Johns Hopkins University

Applied Physics Laboratory)

To make the

trip, the probe will ride atop a Delta 4 Heavy rocket, which is one of the most

powerful operational launch vehicles on Earth (though not quite as powerful as

SpaceX's new Falcon Heavy system).

NASA chose

the rocket because it's surprisingly hard to get to the sun, which is 93

million miles (150 million kilometres) away.

Earth orbits

the sun at a speed of 107,000 kilometres (66,500 miles) per hour, and so does

anything launched off of the planet. To fall toward the sun, PSP will have to

slow down by 85,000 kilometres (53,000 miles) per hour, NASA said in a video

about its mission.

Three

different rocket stages (one firing after the other runs out of fuel) in the

Delta 4 Heavy will help considerably with boosting PSP toward that goal, but

it's not enough to repeatedly fly the probe close to the sun.

Instead, the

rocket will shoot the probe on a path toward Venus, a planet it will fly past

seven times over six years. The world's strong gravitational field will help

gradually absorb PSP's "sideways motion" imparted by Earth and direct

it closer and closer to the sun.

The

consequence of this orbital dance is that PSP will fall toward the sun faster

and faster after each pass. On its first orbit of the sun in November 2018, the

probe will be some 15.4 million miles (25 million kilometres) from the sun.

About 21

orbits later, in December 2024, it will sneak within 4 million miles (6.4

million kilometres) of the sun, travelling at a speed of nearly 692,000

kilometres (430,000 miles) per hour relative to the star.

Achieving

such a velocity would make PSP the fastest a human object in space.

It's nearly

120 miles (193 km) per second – fast enough to fly from New York to Tokyo in

less than a minute – and 3.3 times as fast as NASA's Juno spacecraft, which

zips past Jupiter at speeds of 209,000 kilometres (130,000 miles) per hour.

How to fly

through hell and back

During its

journey, PSP must withstand sunlight 3,000 times more powerful than occurs at

Earth. Outside the spacecraft, in the outer fringes of the sun's corona or

atmosphere, temperatures may reach 1,371 degrees Celsius (2,500 degrees

Fahrenheit)– hot enough to liquify steel.

The probe

also must contend with a "solar wind" of charged, high-energy

particles that can mess with electronics.

The key to

protecting the probe, as well as its sensors for measuring the sun's magnetic

fields and solar wind, is a special heat shield called the Thermal Protection

System.

Made of 4.5

inches (11.5 centimeters) of carbon foam sandwiched between two sheets of

carbon composites, the eight-feet-wide shield will absorb and deflect solar

energy that might otherwise fry the probe.

A water

cooling system will also help prevent the spacecraft's solar panels from

roasting and keep the spacecraft a cosy 85 degrees Fahrenheit (29 degrees

Celsius).

PSP's

mission is to crack two 60-year-old mysteries: why the sun has a solar wind at

all, and how the corona – the star's outer atmosphere – can heat up to millions

of degrees.

Both factors

are key to understanding what leads to potentially devastating solar storms.

"That

defies the laws of nature. It's like water rolling uphill," Nicola Fox, a

solar physicist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory,

said during a NASA briefing in 2017.

"Until

you actually go there and touch the sun, you can't answer these questions,"

said Fox, who's a project scientist for the new mission.

You can

watch the Parker Solar Probe launch toward the sun on Saturday August 11,

around 3 am EDT via NASA TV.

The probe's

mission will end many years from now, after it runs out of the propellant it

needs to keep its heat shield pointed at the sun.

When that

happens, the star's blistering heat will burn up "90 percent of the

spacecraft," science writer Shannon Stirone said on Twitter – but not the

heat shield itself.

"The

heat shield will then orbit the sun for millions of years," she said.

This article

was originally published by Business Insider.

Post A Comment:

0 comments: